Programme Note

This work has been commissioned by the Swansea Festival with funds made available by the Welsh Arts Council, and it in celebration of European Music Year.

Such is the unpopularity of new music that opportunities for composers to write and hear extended works for large forces are sadly infrequent. Firstly, then, may I extend my thanks to the Director and Committee of the Swansea Festival who, with funds from the Welsh Arts Council, have commissioned this work and, moreover, to BBC Wales who in assisting with the copying of the musical material have facilitated its first performance.

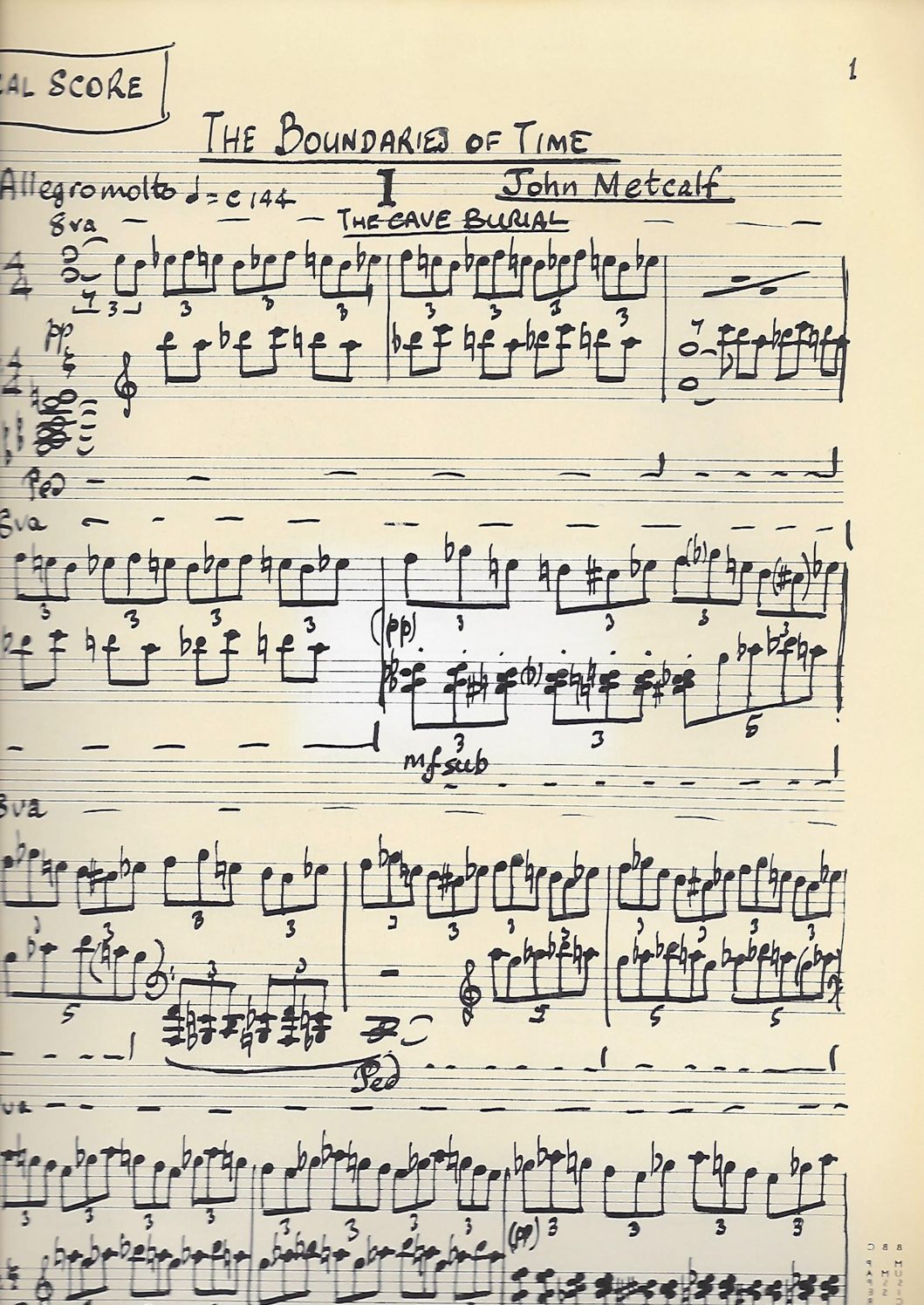

The subject matter of The Boundary of Time concerns man in relation to his environment. It opens with a man buried in a cave overlooking what were once his hunting grounds and are now flooded following a cataclysmic climate change. With this figure as commentator the work proceeds firstly to show early man at odds with the environment, afflicted by disease, a victim of natural disasters, at the mercy of the elements. An imagined and imaginary equilibrium of man with the natural world is presently reached at the centre point of the work. This then leads into a second part where, conversely, man is perceived as the threat by means of pollution, over-exploitation of resources, and, ultimately, weapons of mass destruction. The mirror form is completed by showing at the end a man in a shelter.

Why write such a work at this time? Would it not be more acceptable to choose an easier, more optimistic, subject matter. Or perhaps it is better asked why not? At this point I have to say that I belong to the growing number who believe that issues we face today are too pressing, too urgent to be neglected in our contemporary arts. Historicised subject matter has, admittedly, served oratorio well in the past but let us not question that, for our arts to be construed as living, they must be about our experience today.

My own experience of this work was formed during a stay at Gregynog Hall, Newtown as Gregynog Arts Fellow in 1984. Though I did not begin to write it until I had left Gregynog, my impressions of the soft, idyllic beauty of the Mid Wales countryside reinforced powerful feelings, which many tonight will share, about the remarkable beauty of this country. To be keenly aware of that beauty and to recognise the threat to it (once more, I feel certain, I am not alone) is to set up an unbearable tension, which is at the very heart of The Boundaries of Time. Within the means available to me – a possibly outmoded form, the abstracted musical techniques of late twentieth century music – I have tried to express and affirm that beauty as well as the threat to it. I hope it may speak directly to you. – Note by John Metcalf

When John Metcalf asked me to write the words for a cantata on the theme of the environment, one of my major concerns was to avoid the unfortunate connotations of the word – for, like him, I believe that the preservation of what I would prefer to call our natural heritage, and the wider context of what we are doing to ourselves, is perhaps the most pressing problem that faces us today.

The world around us is, indeed, a heritage, and I wanted to include the idea of the continuity of the relationship between man and nature that is now under threat. There is therefore a sense of historical progress in the set of poems, that fall into two halves. The first describes nature influencing man, and opens with a Neolithic cave burial – inspired by a cave in Gower, used by man at a time when the Bristol Channel was a fertile plain rather than a body of water. The inspiration for the second poem came from the fourteenth century plagues, for the fourth from the age of the metaphysical poets, when the equilibrium between man and nature was perhaps at its zenith.

The second half, following the central orchestral interlude, is a deliberate mirror-image of the first. Here the poems reflect the present day, when man is influencing nature rather than the other way around. It ends, not with a cave burial, but man underground in a shelter, unclear or otherwise. It might also be noted that the cycle hints at the passing of the year, opening with winter, through spring, summer, and autumn, and back to winter again.

Finally it is probably worth saying that these words were written specifically to be set to music: a very different discipline from the writing of poetry to be read aloud or on the printed page, and one demanding a different choice of words and phrasing. – Note by Mark Morris