Programme Note

The idea for the ‘Cello Symphony’ was initiated by Raphael Wallfisch at the 1999 Vale of Glamorgan Festival when Raphael was soloist in a concert in Llandaff Cathedral which included my own work ‘Paradise Haunts . . .’ After the performance we discussed the possibility of a commission and the process was set in motion.

On the practical side progress was fitful, and despite the commitment and persistence of William Boughton and the English Symphony Orchestra it was some time before generous support from the David James Foundation and the Performing Rights Society ensured funds to assist the commissioning of the work. In the meantime I had many ideas for the piece and had begun work. This and the sheer scope of ‘Cello Symphony’ help to explain the extended period of composition.

From the outset I was, however, clear about the approach I wanted to take. I was keen to avoid the particular nineteenth century associations of solo instrument with orchestra, embodied in the concerto form. These associations, implying the setting in strong relief, or even opposition, the individual against the mass seem to me harder to realise at the present time in their most overt form. Aside from this philosophical question, there was also the more immediate technical question of ensuring that the cello – a middle register instrument – be heard above the orchestra. One can only marvel at the success of Elgar and Dvorak in achieving this.

So I decided on a different approach, namely that the solo instrument would often emerge from a ‘community’ of fellow instruments – an honoured guest among equals rather than a potential combatant. This is one of the reasons for the title symphony rather than concerto. To this end I then divided the orchestral celli into 4 and the contrabass into 2 and rather than clearing out the middle range of the orchestra I took the opposite step of adding optional parts for wordless male voices and organ. In a final specific choice of orchestral colouring, I adopted the orchestral forces of the Mozart Requiem – clarinets, bassoons, trumpets and trombones, with the addition of flutes and harp.

These choices are intended to emphasise the lyric and sometimes solemn nature of the work as well as its connections with Wales. In the light of them, I have allowed where necessary for the subtle amplification of the solo part.

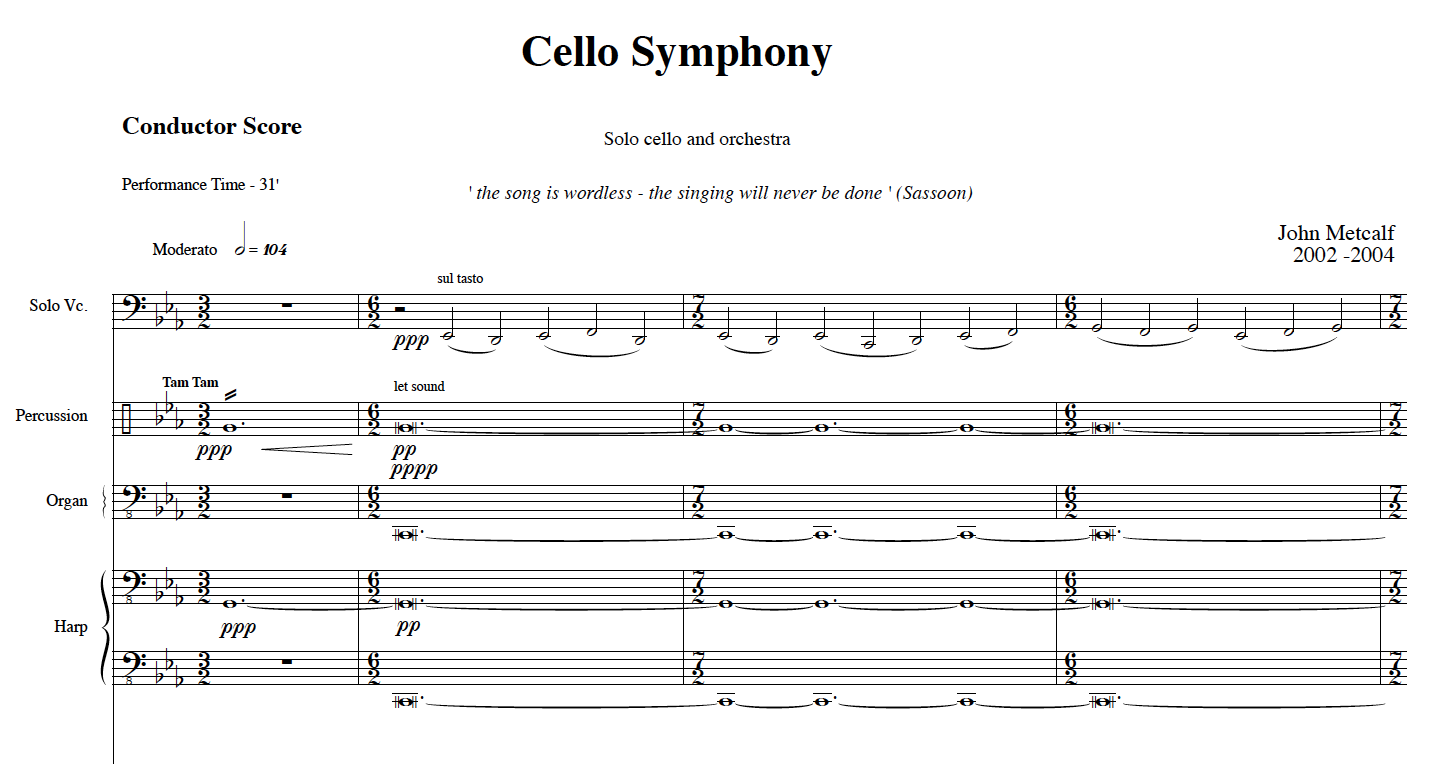

In structure the work is straightforward. ‘Cello Symphony’ is in three clearly defined sections, played without a break, and lasts a little over thirty minutes. All the tempi are related and the piece is ‘modal’ throughout to E flat major/C minor.

Here are a few pointers for the first time listener:

The work opens quietly with the solo cello above a pedal bass. It has for me the character of a journey by night on foot or at sea. As the orchestra celli and voices and other instruments join, the solo instrument is ‘lost from view’ in a swelling crowd and the music builds over several minutes to a climax. A trumpet solo ‘invites’ the solo cello to ‘speak’ and a declamatory and rhapsodic solo passage with orchestra follows. At the end of this passage the music dies away and reverts again to an echo of the opening with bassoons and voices over the pedal base.

A short linking solo passage follows for solo cello accompanied by orchestral celli playing pizzicato. The second section opens with all the celli playing solo lines in a gentle rocking, elegiac passage. This again builds as other instruments join and an extended dramatic passage of music follows. A sudden very quiet moment with solo instrument above muted trombones heralds the end of the second section.

The third section opens with the whole orchestra in chordal writing. A massive fortissimo leads to the reintroduction of the solo instrument using musical ideas which recall the first section. The rhapsodic character of the music continues and leads to the statement of a broad romantic melody first by the cello then the whole orchestra. This carries the music on towards its conclusion where the voices, which up to then have had a subliminal, colouristic role, are heard prominently in the texture for the first time.

I have prefaced the work with a quotation from Siegfried Sassoon (1886-1967) about birdsong heard from the trenches in the First World War:

‘The song was wordless – the singing will never be done’.